When she launched her second mandate as president of the European Commission, Ursula von der Leyen pledged to “make Europol a truly operational police agency and more than double its staff over time”.

As it awaits a major reform proposal scheduled for mid-2026, Europol is steadily consolidating its role as an indispensable data-analysis hub for national law enforcement bodies across the EU and beyond. Decisions taken within the agency increasingly shape policing practices in every member state.

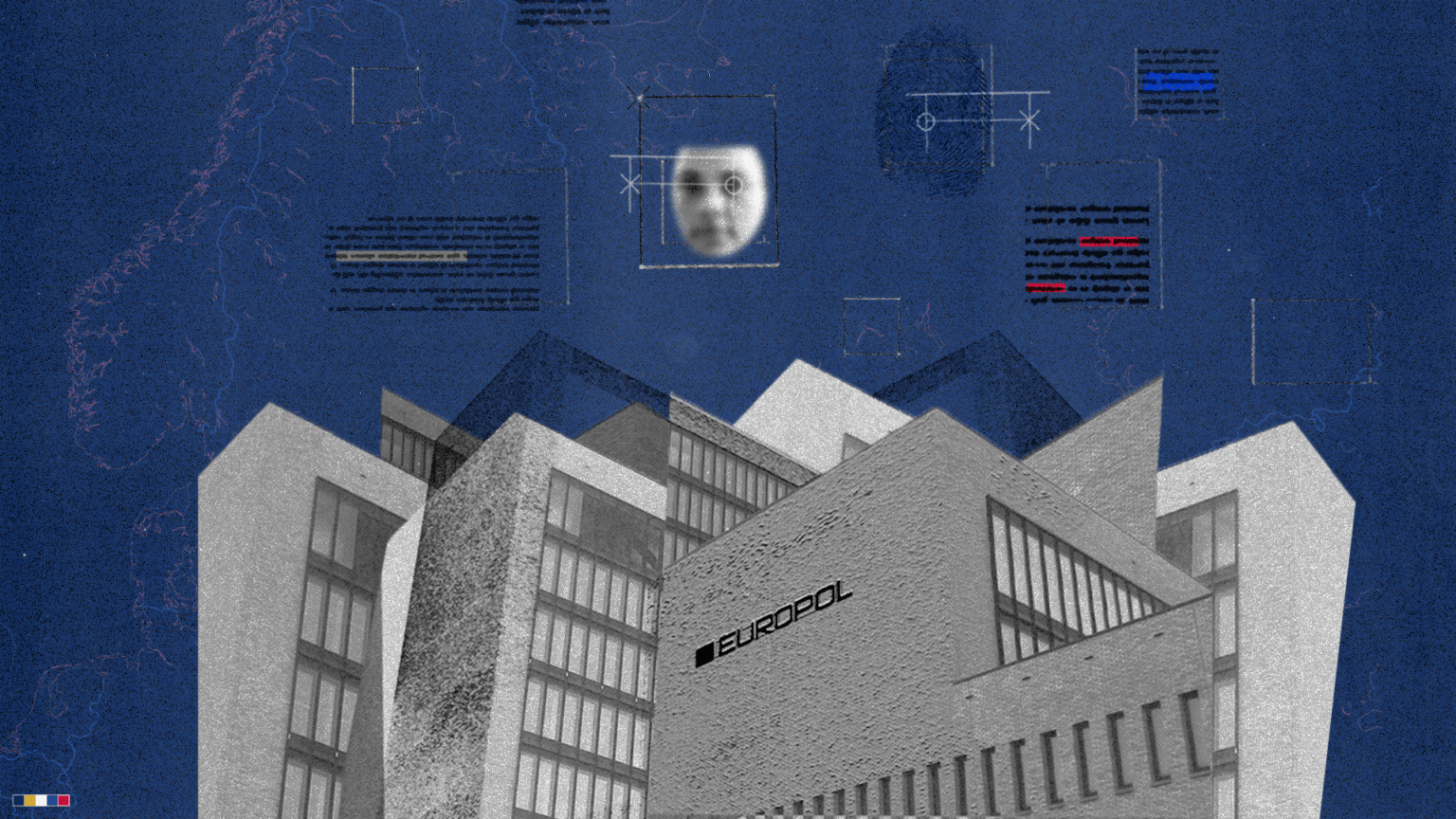

This investigation sheds light on Europol’s secretive data-collection and analysis programmes developed over recent years — often on shaky legal foundations and with limited democratic oversight.

Drawing on extensive analysis of internal documents obtained through freedom-of-information requests, as well as interviews with key sources in EU institutions, law enforcement, academia and civil society, the publications uncover new details about Europol’s research and innovation initiatives and its deepening cooperation with Frontex, the European Border and Coast Guard Agency.

Since 2022, Europol has been authorised to launch innovation projects that harness machine-learning tools to search its rapidly expanding data archives. Two major operations in 2020 and 2021 alone brought roughly 87 million messages from previously encrypted communication services into Europol’s databases. This influx has accelerated efforts to deploy artificial-intelligence systems capable of trawling through vast datasets to analyse criminal activity.

Yet these developments carry significant risks for fundamental rights. Programmes such as a new facial recognition system and an AI-based classifier for images related to child sexual abuse have been launched with minimal scrutiny from oversight bodies.

Europol has also withheld key information on many of its programmes and 25 “AI models” with potentially far-reaching implications for privacy, prompting the European Ombudsman to open several inquiries.

Meanwhile, as the agency aggregates data from national police forces and private actors, it has also received personal information about migrants, refugees and people working along the EU’s borders — including journalists and activists.

In May 2023, the European Data Protection Supervisor (EDPS) concluded that Frontex had unlawfully transmitted operational personal data to Europol for years, including information from humanitarian NGOs, which has been feeding into Europol’s databases since 2016 under the so-called PeDRA programme.

Following an EDPS order, Frontex has been required since to strictly regulate this data collection and transfer. Nevertheless, Europol has continued to advocate for broader access to Frontex’s datasets.

See the stories below.