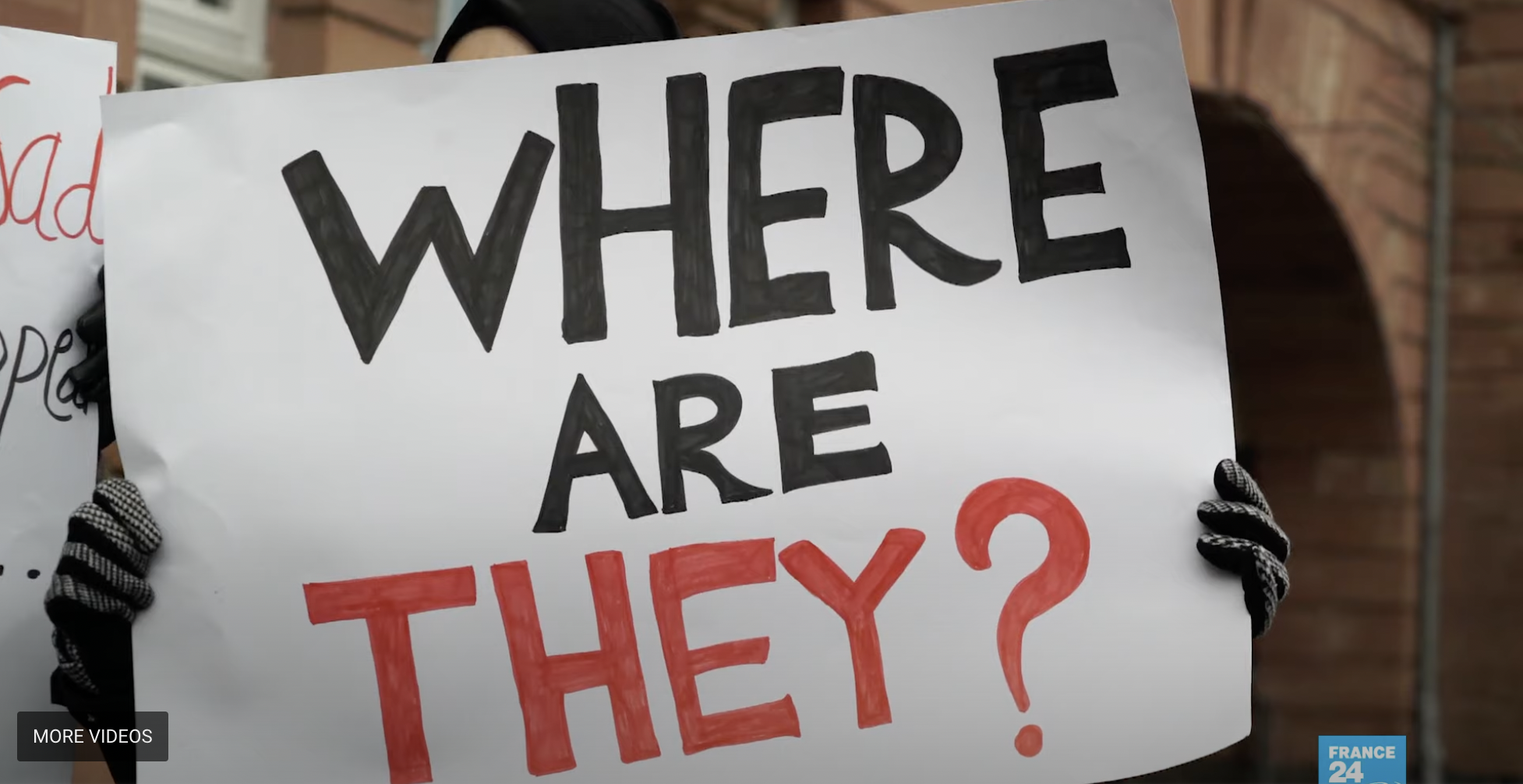

More than 11 years after the start of war in Syria, there is still no international court involved in prosecuting the grave crimes that have been committed. Referral to the International Criminal Court has been blocked in the UN Security Council by Russia and China. But slowly, a path to justice for Syrian victims is starting to take shape.

With more than a million Syrians in Europe, some perpetrators of war crimes and crimes against humanity have also slipped in. These individuals are now being tracked down and prosecuted for their crimes in local courts across Europe.

The principle of universal jurisdiction — which allows particularly serious international crimes to be prosecuted anywhere — is allowing public prosecutors to try Syrian war criminals in courthouses in places ranging from the picturesque German city of Koblenz to the Swedish capital, Stockholm.

This cross-border investigation aimed to shed light on how these cases come about, how they are built and finally brought to trial.

In the absence of an international court, Syrian war crimes are being prosecuted by courts in Europe. Last week, an intelligence officer was convicted for crimes against humanity. @MarinePradel and I followed some of the people who put the case together https://t.co/y4DRj3WIem

— Fernande van Tets (@Fernande_VT) January 22, 2022

The journalists involved spoke with specialist units of national police departments, prosecutors, Syrian survivors, activists and lawyers, NGOs working on justice and accountability and the head of the UN’s mechanism for Syria.

The investigation found that there have been at least 32 convictions for war crimes or crimes against humanity in national courts in Germany, Sweden, the Netherlands and Hungary. Crimes included murder, torture, the enslavement of Yezidi women, the recruitment of child soldiers and posing with corpses.

The majority of cases are against members of the Islamic State and other groups fighting the Syrian regime. Only three concerned individuals affiliated with Damascus, despite the regime being responsible for the vast majority of deaths in the war. The team wanted to understand why.

Germany is taking a leading role in terms of universal jurisdiction prosecutions, as well as targeting regime officials. Two regime officials were convicted in 2021 and 2022 for their role in infamous torture prison Branch 251.

Germany is the only country where there is an ongoing case against a regime-affiliated individual. A Syrian doctor is currently being tried in Frankfurt. Another case against a man who fought with a regime-affiliated militia is expected to start later this year.

One of the challenges in prosecuting crimes committed by regime officials in other European countries is the diversity of requirements for universal jurisdiction.

France, Switzerland and the Netherlands require a perpetrator to be present in the country, or the victim to be a national. Senior regime figures have had little reason to flee since 2015, when Russian air support turned the tide on the Syrian battlefield. Only those who deserted prior to 2015, such as the two officials in Koblenz, are likely to be present on European soil.

Furthermore, many crimes committed on the regime side have not been documented as extensively, meaning that they are harder to prove in court.

Dutch readers, don’t miss this @trouw article by our #IJ4EU grantee @Fernande_VT on the Syrian former intelligence officer sentenced to life today by a German court for crimes against humanityhttps://t.co/t2PP368H9o

— IPI-The Global Network for Independent Journalism (@globalfreemedia) January 13, 2022

The role of evidence gathered by NGOs such as the Commission for International Justice and Accountability, who smuggled evidence out of the country, and briefs by the UN’s III-M have proven vital in proving there was a conflict or the systematic nature of the crimes; a requirement for a crime to be classified as a crime against humanity.

Another obstacle is finding witnesses to testify against regime officials. Syrians are often afraid to come forward and participate in trials. Those with family in Syria have had relatives threatened by the feared secret police, the team found.

Also, Syrian victims need to find a way to the authorities in order to get the ball rolling. Germany is unique in that the European Center for Constitutional and Human Rights, an NGO, has German lawyers available to help Syrian NGOs and activists navigate the German legal system. Countries like the Netherlands lack such a body, meaning that victims — who are often distrustful of the police — don’t know where to turn in order to launch a case.

The team also found the Syrian community to be divided about the importance of these universal jurisdiction trials in the wider search for justice. Many feel they only target low level perpetrators.

Arrest warrants against senior officials such as Air Force Intelligence chief General Jamil al-Hassan and Ali Mamlouk, director of the National Security Bureau and one of Syrian President Bashar al-Assad’s most trusted advisors, have been issued by France and Germany.

Nevertheless, the team discovered that the tide is turning. Encouraged by the cases in Germany, other countries, including Sweden, France and the Netherlands, are working on cases against regime officials.

This is an ongoing investigation.