This cross-border investigation examines the fast-growing industry of “chemical recycling” of plastics, presented as a “circular” solution to the plastic pollution problem. It found that some packaging marketed as containing high levels of recycled plastic may include only trace amounts in reality.

The team analysed everyday consumer products sold in European supermarkets — including Magnum ice cream, Philadelphia cheese, Heinz Beanz, Nivea body care items, Delizio coffee, Kind chocolate and Garofalo pasta.

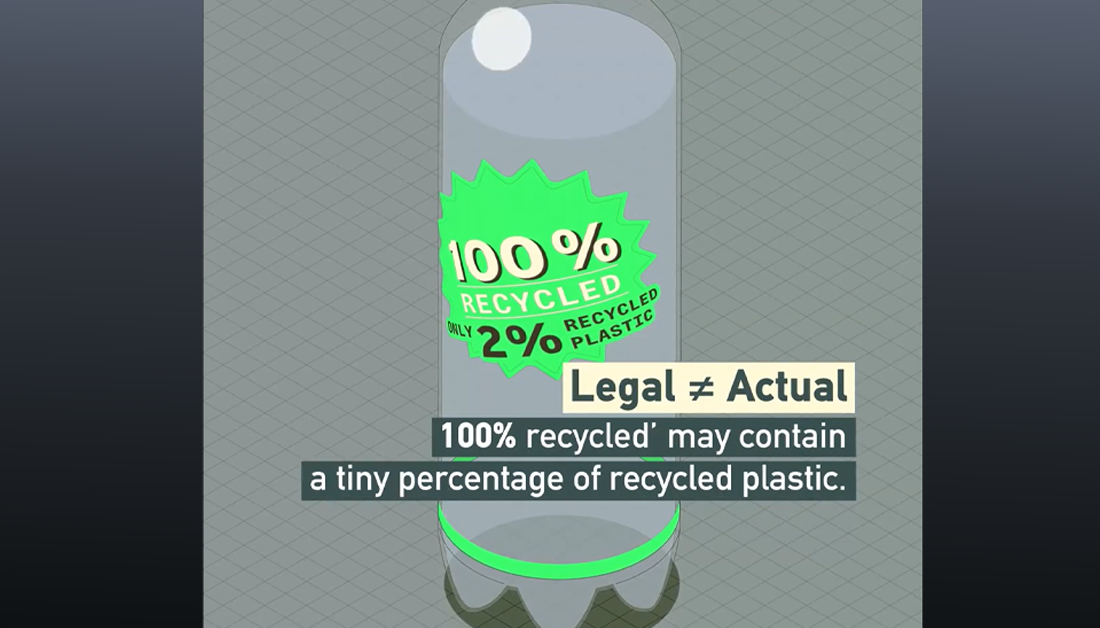

These goods, produced by major brands such as Unilever, Mondelez, Mars, Kraft Heinz, Beiersdorf (maker of Nivea), Delica and Garofalo, are sold in packaging labelled as containing between 30% and 100% “recycled plastic”. However, supply-chain analysis showed that the actual share of recovered polymers does not exceed around 5%. The remainder is derived from virgin fossil feedstock, primarily naphtha.

This product packaging originates from SABIC, the chemicals arm of oil giant Saudi Aramco. Like other major petrochemical firms, SABIC markets part of its output as “circular” and climate-friendly. The investigation found that, in practice, these plastics — produced through chemical recycling technologies — remain overwhelmingly fossil-based.

At the heart of the issue is an accounting method known as “mass balance”, used under certification schemes such as ISCC (International Sustainability and Carbon Certification). Under this system, “recycled content” can be allocated on paper across batches of plastic based on overall inputs and estimated yields, rather than the physical share of recycled material in each product.

In simplified terms, if a production stream uses a mix of fossil and recycled feedstock, companies can label some final products as “100% recycled” and others as fully virgin — regardless of their actual composition.

Independent experts interviewed by the team described this practice as misleading and a form of greenwashing.

Despite these concerns, the European Commission is moving to regulate — and in part legitimise — the use of mass balance to support the development of chemical recycling technologies.

Chemical recycling processes, including pyrolysis and solvent-based methods, break plastic waste down into monomers that can be used to produce new polymers. Industry promotes chemical recycling as a solution for plastic types that cannot be processed through conventional mechanical recycling.

The investigation found major technical and environmental limitations.

In the United States, eight of 11 active chemical recycling plants reportedly burn the resulting plastic-derived oil as fuel instead of turning it back into new plastic.

The most common process, pyrolysis, can only introduce small shares of recycled input into conventional steam crackers because pyrolysis oil is corrosive and typically limited to around 5% of feedstock. Moreover, only about 40% of the output from pyrolysis becomes monomers suitable for new plastic production.

Climate impact assessments reviewed by the team indicate that pyrolysis can emit more CO₂ than producing plastic from virgin oil, and up to nine times more than mechanical recycling.

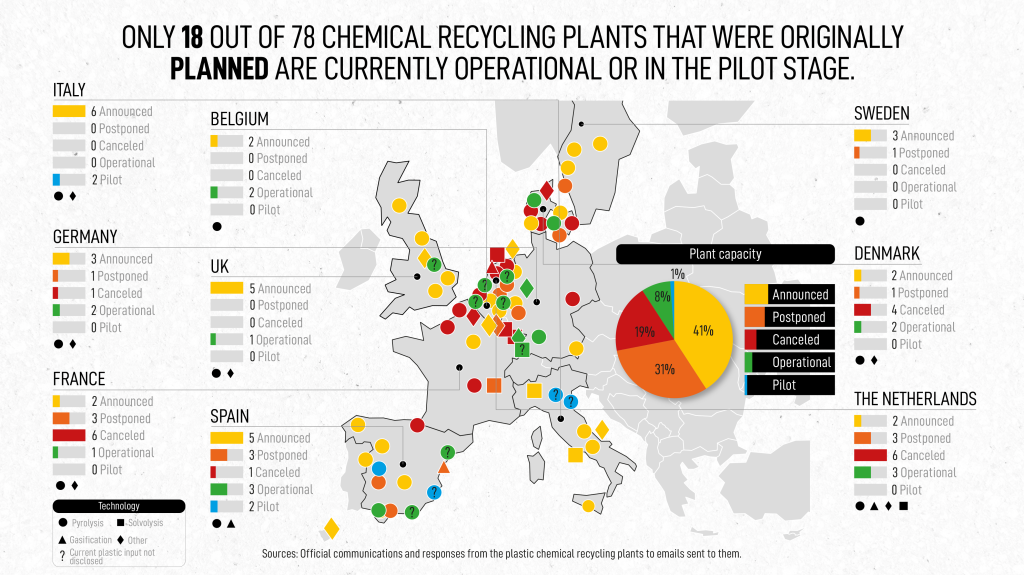

The team also mapped the real-world rollout of chemical recycling in Europe.

Of 78 plants announced in recent years across Italy, France, Spain, Germany, Belgium, the Netherlands, Denmark, the United Kingdom and Sweden, only 18 are operational. Four of these run only intermittently as pilot projects.

While announced, cancelled and delayed projects together claim a theoretical capacity of 2.5 million tonnes per year, the operational and pilot plants together amount to just 0.24 million tonnes. Of the 14 plants actually running, only six have publicly disclosed how much plastic they process annually. None provided Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) documents underpinning their claimed emissions savings.

The investigation further found that key environmental data remain inaccessible.

The European Commission has declined to release LCA information, even after the matter was raised with the European Ombudsman. This includes projects that received EU financial support.

Based on the team’s calculations, roughly €760 million in EU grants and equity investments have been directed to chemical recycling projects, with around two-thirds of this funding linked to pyrolysis. Nearly half supports facilities connected to the supply chains of the world’s 14 largest petrochemical companies or their affiliates.

The investigation raises serious questions about the environmental credibility, scalability and transparency of chemical recycling — and about the accuracy of “recycled plastic” claims now appearing on supermarket shelves across Europe.